Continuous mapping theorem

In probability theory, the continuous mapping theorem states that continuous functions are limit-preserving even if their arguments are sequences of random variables. A continuous function, in Heine’s definition, is such a function that maps convergent sequences into convergent sequences: if xn → x then g(xn) → g(x). The continuous mapping theorem states that this will also be true if we replace the deterministic sequence {xn} with a sequence of random variables {Xn}, and replace the standard notion of convergence of real numbers “→” with one of the types of convergence of random variables.

This theorem was first proved by (Mann & Wald 1943), and it is therefore sometimes called the Mann–Wald theorem.[1]

Contents |

Statement

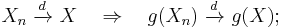

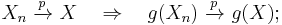

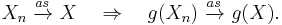

Let {Xn}, X be random elements defined on a metric space S. Suppose a function g: S→S′ (where S′ is another metric space) has the set of discontinuity points Dg such that Pr[X ∈ Dg] = 0. Then[2][3][4]

Proof

Spaces S and S′ are equipped with certain metrics. For simplicity we will denote both of these metrics using the |x−y| notation, even though the metrics may be arbitrary and not necessarily Euclidian.

Convergence in distribution

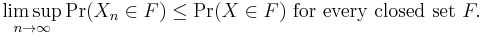

We will need a particular statement from the portmanteau theorem: that convergence in distribution  is equivalent to

is equivalent to

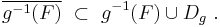

Fix an arbitrary closed set F⊂S′. Denote by g−1(F) the pre-image of F under the mapping g: the set of all points x∈S such that g(x)∈F. Consider a sequence {xk} such that g(xk)∈F and xk→x. Then this sequence lies in g−1(F), and its limit point x belongs to the closure of this set, g−1(F) (by definition of the closure). The point x may be either:

- a continuity point of g, in which case g(xk)→g(x), and hence g(x)∈F because F is a closed set, and therefore in this case x belongs to the pre-image of F, or

- a discontinuity point of g, so that x∈Dg.

Thus the following relationship holds:

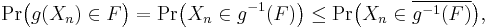

Consider the event {g(Xn)∈F}. The probability of this event can be estimated as

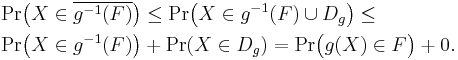

and by the portmanteau theorem the limsup of the last expression is less than or equal to Pr(X∈g−1(F)). Using the formula we derived in the previous paragraph, this can be written as

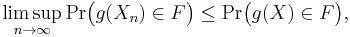

On plugging this back into the original expression, it can be seen that

which, by the portmanteau theorem, implies that g(Xn) converges to g(X) in distribution.

Convergence in probability

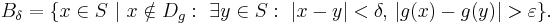

Fix an arbitrary ε>0. Then for any δ>0 consider the set Bδ defined as

This is the set of continuity points x of the function g(·) for which it is possible to find, within the δ-neighborhood of x, a point which maps outside the ε-neighborhood of g(x). By definition of continuity, this set shrinks as δ goes to zero, so that limδ→0Bδ = ∅.

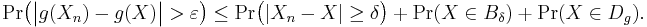

Now suppose that |g(X) − g(Xn)| > ε. This implies that at least one of the following is true: either |X−Xn|≥δ, or X∈Dg, or X∈Bδ. In terms of probabilities this can be written as

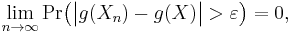

On the right-hand side, the first term converges to zero as n → ∞ for any fixed δ, by the definition of convergence in probability of the sequence {Xn}. The second term converges to zero as δ → 0, since the set Bδ shrinks to an empty set. And the last term is identically equal to zero by assumption of the theorem. Therefore the conclusion is that

which means that g(Xn) converges to g(X) in probability.

Convergence almost surely

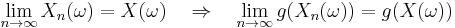

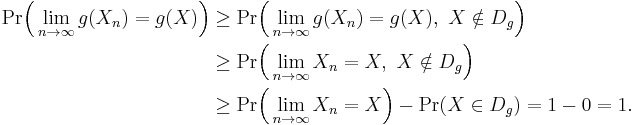

By definition of the continuity of the function g(·),

at each point X(ω) where g(·) is continuous. Therefore

By definition, we conclude that g(Xn) converges to g(X) almost surely.

See also

References

Literature

- Amemiya, Takeshi (1985). Advanced Econometrics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674005600. LCCN 1985 HB139.A54 1985.

- Billingsley, Patrick (1969). Convergence of Probability Measures. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471072427.

- Billingsley, Patrick (1999). Convergence of Probability Measures (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471197459.

- Mann, H.B.; Wald, A. (1943). "On stochastic limit and order relationships". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 14 (3): 217–226. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177731415. JSTOR 2235800.

- Van der Vaart, A. W. (1998). Asymptotic statistics. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521496032. LCCN .V22 1998 QA276 .V22 1998.

Notes

- ^ Amemiya 1985, p. 88

- ^ Van der Vaart 1998, Theorem 2.3, page 7

- ^ Billingsley 1969, p. 31, Corollary 1

- ^ Billingsley 1999, p. 21, Theorem 2.7